“Searing bullets and bloodstained knives”

Liberation and decolonial psychologies in the Material Turn.

Did you hear?

It is the sound of your world collapsing.

It is the sound of our world resurging.

The day that was day was night.

And night will be the day that will be day.

—ZAPATISTA SUBCOMANDANTE MARCOS1

In the Fall of 2024, I was flipping through the latest issue of American Psychologist, the American Psychological Association’s flagship journal.

The first article, a presidential paper from Dr. Thema Bryant, caught my eye: “Lessons from Decolonial and Liberation Psychologies for the Field of Trauma Psychology.”2

Bryant, also a tenured professor at Pepperdine University and ordained elder in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, has made decolonizing the psychology profession a primary effort for her APA presidency, and this paper fits solidly within broader societal trends towards decolonization.

As I read the abstract, however, I was struck by unusually strong radicalism, barely hidden behind vague and academic language.

Bryant described liberation and decolonial psychologies as “awakening” her to “conceptualizations and frameworks that center reclamation of a form of holistic healing and empowerment for trauma,” citing “sociopolitical pathways for survivors to reclaim themselves.”

In plain language, this means that liberation and decolonial ‘psychologies’ (Communist revolutionary practices oriented to violent uprising) will help those “traumatized” by “colonialism” (everyone) to free themselves through their participation in the revolution.

I noticed she repeatedly used the phrase “pathways they illuminate” to describe these revolutionary practices, word choice that immediately evoked the Peruvian Marxist guerrilla group The Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso).

For those who aren’t familiar, the name comes from a maxim of the founder of the Peruvian Communist Party:

El Marxismo-Leninismo abrirá el sendero luminoso hacia la revolución" ("Marxism–Leninism will open the shining/luminous path to revolution").3

I have no idea if this was intentional. But the context was odd, to say the least, and it stuck out to me so distinctly.

Alongside other liberation clinical frameworks, she also cited practices like “problem-solving coping,” meaning activism and “resistance strategies.” This includes, among other things, “confronting the persons perpetrating the stress and trauma of oppression,” which can include entire demographics of people.

Once one considers the grounding in a Fanonian psychology of oppression and Ignacio Martín-Baró’s liberation psychology, the implications become quite astounding.

When I realized that this level of radicalism was flying under the radar, I knew I needed to find a way to communicate the seriousness of this agenda in counseling and psychology, including to other clinicians.

Importantly, this is not just one paper from one (albeit prominent) person, but a coherent effort led by academia and professional bodies to deploy these ‘psychologies’ (radicalizing strategies) within the context of an ongoing revolution that has advanced to a new stage, often termed the “Material Turn.”

This ‘turn’ began around late 2023/2024 and coincides with the 2024-2026 United Nations 2.0 “turbocharger” for the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, the end goal of which is a Dengist-style global synthesis of communism and fascism. Goal 10, reducing inequalities within and between countries, is particularly relevant here.

As you observe North American elite academia and DEI bureaucracy collapse around you, consider that this is likely a necessary part of a strategy to shift power and reorient the target onto economic and material concerns (especially class, ‘blood and soil’ nationality/race, and sustainability).

Now, you’ll see greater inclusion of foreign sources in North American academia, increased concern about immigration and nationality (which will be connected to ‘unsustainable’ environmental and economic issues), and a focus on populist class solidarity and struggle.

Due to the nature of these concerns, this is likely to coincide with destabilization and a more violent struggle ‘on the ground,’ and understanding how decolonial and liberation psychologies are deployed in this context is critical.4

Thus, the following is my current best effort to condense what could be a book’s worth of information and analysis into no more than a one-hour read, with the hope that it is reasonably accessible without compromising a comprehensive picture.

With respect to those who don’t have time for this piece, I will also highlight and elaborate on key points in separate posts.

Here, you will learn that liberation and decolonial psychologies are parallel and interrelated movements to facilitate sociopolitical and cultural “reclamations,” respectively, and are framed as liberatory (salvific) through collective action (Communist revolution).

Decolonial psychology, often used interchangeably with “Indigenous psychology,” is grounded in a Fanonian psychology of oppression and targets the “Western” knowledge base of counseling and psychology, including (logos-based) talk therapy and DSM diagnoses.

Instead, a ‘holistic’ Indigenous Science is employed, relating various so-called ‘crises’ to an environmentally harmful and ‘extractive’ capitalism said to be grounded in false Western beliefs about individualism and freedom.

Thus, mental health in decolonial psychology requires 1.) awakening to our true socialist nature that colonialism has estranged us from, and 2.) participating in necessarily violent revolution to overcome these colonial systems of oppression.

Likewise, liberation psychology comes out of Latin American liberation theology and the materialist ‘analectic’ turn of Community Social Psychology, making it ultra-radical and teleologically oriented to violent class-based struggle as a necessary precedent for ‘true’ liberation.

It is deployed alongside decolonial psychology to facilitate this salvific revolutionary action through tried-and-true radicalization strategies (e.g., “recovering historical memory,” Freirean conscientization, “de-ideologization”) that focus on collective identity and activist power.

In the context of the Material Turn of the revolution, these ‘psychologies’ can effectively exploit existing Woke intersectionality issues and reorient them to more materialist issues like immigration, capitalism, and the environment.

This makes them especially effective not only with the most materially and psychologically vulnerable, but also those who are already ‘in the cult,’ so to speak, as a means of increasing radicalization.

Importantly, both are paradigmatically grounded in, and teleologically oriented to, social uprising that explicitly and necessarily includes terrorism, violence, and disorder.

Taken together, this paints an incredibly concerning picture of the role of counseling and psychology in the unfolding revolution, and will have serious consequences for all involved.

If this concerns you, please consider reading further.

The Liberation Paradigm

“History is no longer as it was for the Greeks, an anamnesis, a remembrance. It is rather a thrust into the future.” - Gustavo Gutiérrez

Latin American Liberation Theology

First, it’s important to understand that liberation psychology is “not a branch of psychology, but a psychological branch of the liberation paradigm,” meaning the liberation paradigm that was developed predominantly by liberation theologians in Latin America.5

Thus, to understand anything about liberation psychology, we must first understand liberation theology.

Before we begin, please note that one of the primary characteristics of liberation theology is that it is contextualized. This means that liberation theologies arise from time-and-space-bound locations where experiences of oppression (and subsequent reflections-on-actions) occur, with an emphasis on praxis over theory.

However, identifiable developments and stable beliefs/practices can be discerned, and most of them derive from this primary source in the post-Vatican II Latin American context.

For our purposes here, I will capitalize Liberation Theology to denote its Latin American practice, where it was most heavily codified and adapted by figures such as Enrique Dussel (philosophy), Gustavo Gutiérrez (theology), Ignacio Martín-Baró (psychology), and Paulo Freire (pedagogy).

When speaking of similar or parallel theologies emerging, for example, in Black American or Islamic contexts, I will identify them as countable nouns using lowercase (e.g., a liberation theology).

Vatican II

No discussion of Latin American Liberation Theology can occur without the precedent of the sweeping changes in the Catholic Church in the Second Vatican Ecumenical Council (Vatican II), initiated by Pope John XXIII in 1962 until 1965.

While I cannot possibly begin to adequately cover this topic, for our purposes here, we can say that the various theological reforms brought on by Vatican II, especially in its Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium) and the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World (Gaudium et Spes), provided the contextual soil within which Liberation Theology could take hold in Latin America under the guise of Catholicism.6

This includes new emphases on:

The Church’s solidarity with humanity, especially the poor and marginalized, adapted by Liberation Theology into the Church as an agent for social change against systemic injustice (“structural sin”).

The Church’s mission to serve all people, especially the oppressed (see Lumen Gentium), subversively adapted by Liberation Theology into the “preferential option for the poor,” meaning the solidarity with the poor (proletariat) by pursuing systemic change (revolution).

Collegiality, encouraging bishops to address local issues in a more decentralized and locally adapted manner, empowering Latin American bishops and theologians to practice contextualized liberation theology.

The Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation (Dei Verbum), which sought renewed engagement with the Bible, especially as it relates to addressing social issues. This opened the door for Liberation Theology to interpret the Exodus narrative and prophetic traditions as a call for liberation from oppression.

The teaching that all Christians are called to holiness and active engagement in the world, which Liberation Theology uses to encourage lay participation in revolution.

Dialogue with the modern world and other ideologies, empowering Liberation Theology’s engagement of Marxism as an analytical tool (sound familiar, SBC?) to address systemic injustice.

Sacrosanctum Concilium, liturgical reform towards accessibility and integration with local culture, which would support Liberation Theology’s contextual practices.7

While these changes are nonetheless important, I want to be clear that this is ultra-simplified for basic background, and that I am in no way making an assessment as to their value, context, or orthodoxy.

For our purposes, the most important thing to understand is that liberation theology grew out of the contextual Latin American response to these reforms brought on by Vatican II.

Medellín Conference

“We are at the beginning of a new historic epoch in our continent. It is filled with the hope of total emancipation – liberation from all servitude – personal maturity and collective integration. We foresee the painful gestation of a new civilization.”8

In 1968, the Second Episcopal Conference of Latin America was held in Medellín, Columbia (“Medellín Conference”) by the Catholic Bishops of Latin America (CELAM) with the aim of interpreting Vatican II in the specific Latin American context. This led to the production of its core document, “The Church in the Present Transformation of Latin America in the Light of the Council.”9

Adopting a dialectical materialist frame for economic issues, the conference condemned structural injustice (structural sin) and denounced Latin America’s economic, political, and cultural dependency on North America and Western Europe.

Most importantly, it called for the Catholic Church (including its laity) to take an active role in liberation, wherein “all men and all peoples ought to feel collectively culpable, commit themselves to conquer the sin within, [and] fight for liberation from [sin’s] consequences (hunger, misery, sickness, oppression, and ignorance).”10

Notice that salvation from the consequences of sin is demanded within immanent reality, something that is arguably unorthodox from a traditional Christian (and especially Catholic) view.

“In Latin America, salvation, which is the realization of the Kingdom of God, involves the liberation of all men, the progress of each and all from a less human condition to one more human. This is what we desire, and this is what we will strive for. To accomplish our goal, we must become imbued with the message of Christ, to understand that the Kingdom of God will not reach its fullness until integral development has been achieved. Therefore, in our pastoral care we will search for the means to manifest the love of the Lord in the Church today.”11

In both this and later conferences, the bishops also developed what is now known as the “preferential option for the poor,” which teaches that the Bible gives priority to the concerns of the poor and oppressed, in part following the theological developments outlined at Vatican II in Gaudium et Spes.12

Importantly, this “preferential option” is somewhat challenging to define. It seems to have two meanings: one for the mainstream Catholic faithful in social teaching and another for more radical liberation theologians, who interpret it within the frame of revolutionary Marxist praxis.

For the Latin American context from which liberation psychology would adapt it into a “preferential option for the oppressed,” it is best understood as the belief that God favors the poor and oppressed in history, and thus members of the church are obligated to adopt the proletariat perspective (the Maoist “People’s Standpoint) and participate in revolutionary activities on their behalf.

This conference was also important for the practice of Christian Base Communities (Comunidades Eclesiales de Base, or CEBs), small autonomous groups that meet for Bible study and grassroots political discussion/organization. These have long been popular in Latin America, Asia, and Africa and serve as disperse grassroots radicalization under the guise of Catholicism.13

Members of these groups were often illiterate and rural, for whom no local church could serve, and would use Paulo Freire’s conscientizing method of literacy (something that we will discuss here soon) that inherently includes revolutionary action.

It's also worth noting that the Latin American context within which this liberationism arose was volatile, with significant political instability, economic inequality, and a historically dominating Catholic Church.

With hindsight and charity, we can understand how Latin America turned to both Communism and Fascism, but we must also understand these were fatal errors that only added to the suffering of the Latin American people, especially its most vulnerable.

It's also easy to see how this can subvert the existing Catholic faith and take advantage of sincere care for the poor and oppressed.

Consider the “preferential option for the poor,” which is now a part of mainstream Catholic Social Teaching (though, as far as I can tell, not without controversy).

As presented to the average Catholic faithful, it is a commitment to putting “the needs of the poor and vulnerable first,” thoroughly grounded in scripture and extensive Church tradition.

In the context of its development through liberation theology, however, it rebrands the Marxist theological belief that the proletariat, by nature of their oppression, has a special claim to reality and must receive immanent salvation from the “consequences of sin” through faithful participation in the revolution.

Pedagogy of Liberation

Working within this milieu, the Brazilian educator Paulo Freire (1921-1997) from Recife also rose to prominence, adapting the “See-Judge-Act” hermeneutical method (and now “foundational pastoral method” of Laudato si’) from the radical Catholic Workers Movement (AKA the Jocists) to facilitate revolutionary participation through education.14

Freire argued that education is either a tool for liberation/humanization or oppression/dehumanization and advocated for a critical constructivist, dialogical participatory model of education. This means that both teacher and student are co-creators of knowledge through a critical examination of their material and sociopolitical conditions.15

Education, then, is a fundamentally liberatory act that must address root causes by raising awareness of systems of oppression and facilitating agency and action to overturn them.

As Brazilian Marxist Antonio Cechin notes, the first to pick up Freire’s method was the Catholic Church through Dom Hélder Câmara, the Archbishop of Recife (AKA “The Red Bishop” and later Klaus Schwab mentor), and it was deployed throughout the countryside with poor and illiterate peasants.16

These literacy circles would ultimately become the foundation for Basic Ecclesial Communities, which were central to facilitating liberation theology among the masses.

Critical Consciousness

This work gave rise to the concept of critical consciousness (conscientização), in which one is awakened (“Woke”) to one's positionality in the matrix of social, political, and economic power/oppression and motivated to act on that awareness toward liberation.

Such conscientization involves a repeated cycle of critical analysis (awareness and critique of systems and structures that create and sustain inequity, like capitalism, racism, sexism, heteronormativity, etc.), critical motivation/agency (learning that one is a historical agent who can facilitate change), and critical action (taking action to address perceived injustices).17

Thus, it’s important to understand that critical consciousness necessarily includes action (revolutionary activism) to transform the systems and structures perceived to be upholding oppression.

We will return to this concept when discussing liberation and decolonial psychologies in practice.

A Theology of Liberation

Theologians and Development

Freire subsequently influenced the primary founder of Liberation Theology Proper, Gustavo Gutiérrez, who interpreted theology as a “critical reflection on praxis.”18

This means that the ‘study’ of God is an ongoing process of conversion (to the side of the oppressed) and salvation (revolutionary movement towards the Kingdom of God on Earth).19

Gutiérrez, a Dominican priest and Catholic theologian in Peru, initially studied medicine at the National University of San Marcos (aiming to be a psychiatrist) before deciding he wanted to become a priest.20

After this, he studied theology in Belgium and France, where his exposure to various thinkers, including Karl Marx, significantly influenced his theological development.

Importantly, this includes Marx’s dialectical theory of class struggle and the material conditions of poverty, which he would incorporate into his ‘Catholic’ framework as an analytical tool.

He was ultimately ordained in 1959 as a Dominican.

In 1971, Gutiérrez published A Theology of Liberation (‘Teología de la liberación’), codifying and expanding it into a more comprehensive theological framework, including by drawing on Marxist dialectical materialism as an analytical method.21

According to Miguel De La Torre, Gutiérrez sought to transform theology from “doctrinal truths created by the intelligentsia for the common people to believe” into a “reflection of actions taken to end human suffering – a critical reflection based on praxis in light of God’s word.”22

“To know God is to do justice [alluding to Jer 22:15-16], is to be in solidarity with the poor person.” – Gustavo Gutiérrez

Thus, it is a praxis theology, meaning that the highest form of knowing is doing. In this case, action must be on the side of the proletariat (The People) to advance History to the Kingdom of God (stateless classlessness, or Communism).

Here, God for Gutiérrez is not known through reason (like Biblical study) or faith (like prayer) but is instead uncovered (primarily in immanent reality) through the critical reflection of these actions.

In addition to Gutiérrez, other names worth knowing include:

Enrique Dussel, Argentinian priest and founder of liberation philosophy. He is also central here and probably deserves an entire section if there were time.

Dussel’s work outlined center-margins (oppressor-oppressed) worldview that necessarily requires revolutionary liberation through the subversion of the established order and “centering” of the periphery.23

Other contributors include Leonardo Boff, a Brazilian and former Franciscan priest, who published Jesus Christ Liberator in 1971, outlining a liberationist Christology where Christ is a liberator from the human condition, and the Kingdom of God that is realized, in part, within (immanent) history.24

“Christ understands himself as Liberator because he preaches, presides over, and is already inaugurating the kingdom of God.” - Leonardo Boff

A particularly prolific author, Boff also published Church: Charism and Power, a critique of institutional monarchical power in the Catholic Church (in his view, rightly undermined by Vatican II with the church as the people of God) and argues for a “pneumatic ecclesiology” and “laical model” born from the grassroots faith of the poor.

“It is not those who are Christians who are good, true, and just. Rather, the good, the true, and the just are Christians.” – Leonardo Boff

Leonardo co-wrote several books with his brother, Servite priest Clodovis Boff, who would spend about half of the year doing pastoral work in the Amazonian jungle. Through these experiences, he developed his “feet-on-the-ground” theology, meaning that it is worked out in practice through the arduous physical experience of the marginalized and poor.25

This is, quite literally, the philosophy of Communist labor camps (gulags) which aim to re-educate victims into the proletariat’s ‘standpoint’ through the brutal experience of hard labor.

Jon Sobrino, a Jesuit theologian in El Salvador (like Gutiérrez), was also focused on Christology, viewing the oppressed as crucified (Scourged Christs) who, like Jesus, “provide an essential soteriological perspective on our history.”26

In this (Marxist) view, God chooses the oppressed, whoever they may be at any given point in history, as the “principal means of salvation,” and those who align with the Empire of the time are subsequently “more aligned with the satanic than with the divine.”27

Another relevant theologian is Juan Luis Segundo, a Jesuit priest from Uruguay, who similarly argued that the mission of the Church is to serve the oppressed through revolutionary praxis.

One of his most significant contributions is the liberationist hermeneutic circle, which interprets the Bible through the lens of the present situation of the oppressed, constructing and reconstructing a theology from liberating praxis bound within one’s context. Here, the Bible is always relevant to present situations, but interpretations must change as reality does.28

While most contributors are within this post-Vatican II Catholic circle, there are a couple of non-Catholic names in the same Latin American liberationist milieu worth mentioning.

One is Argentinian Methodist minister José Míguez Bonino, who was once president of the World Council of Churches. He viewed liberationists as “a new breed of Christians” and advocated (through his organization, Churches and Society in Latin America, ISAL) for a “theology of revolution” that promoted socialist revolution.

Lastly, we have José Porfirio Miranda, an ex-Jesuit Mexican Marxist and Communist militant who explicitly advocated for linking biblical Christianity with Marxism, including Paul with Marx.

According to Miranda (following Mark 10:21, 25; Luke 6:20, and Matt 6:24), entering God’s kingdom requires renouncing private property, and that one must choose between capitalism (money) or communism (God).29

Overall, we can see that Latin American Liberation Theology:

Grafted a Marxist dialectical materialist lens onto ostensible Catholicism.

Is praxis-based in that theology is not the ‘study’ of God from an intellectual or faith-based standpoint but rather a critical reflection on action upon the world, Doing the Work on the side of the oppressed (proletariat).

Functionally deifies the proletariat as Scourged Christs who are the principal means of salvation throughout history and favored by God.

Pursues material salvation from the bondage of sin and its consequences, including hunger, misery, sickness, oppression, and ignorance.

If you are a Christian reading this, I respectfully implore you to be mindful of this heresy in your personal contexts. We are living in Paulo Freire’s world right now, and liberation theologies are much more common than many have noticed.

In addition to its Latin American development, we will briefly review parallel developments worth noting for our purposes here. Keep in mind that this type of ‘theology’ (practice) is contextual and thus develops and redevelops within its time-and-place-bound present.

Parallel Contextual Developments

While there are numerous liberation theologies worth considering, we will briefly review two that I think have primary significance for our purposes here: American Black liberation theology and 20th-century Islamic liberation theology.

Black Liberation Theology

In North America, the most well-known is so-called Black (liberation) theology, developed most prominently by the Methodist minister and long-time Union Theological Seminary professor James H. Cone.

Cone is both highly influential and incredibly controversial, declaring that the “white theology” of mainstream Christianity (e.g., Tillich, Aquinas, Barth, Augustine, Bultmann) was that of the “Antichrist.”30

In 1969, Cone published Black Theology and Black Power, synthesizing the thoroughly radical Marxist Black Power movement into the Gospel, going as far as to claim that Black Power was the Gospel (see the previous section for heretical parallels).

A year later (and just one year before Gustavo Gutiérrez published his similarly titled book), Cone published A Black Theology of Liberation, where he asserted that “God is [politically] Black” because he sides with the marginalized and oppressed in their fight for liberation.31

As noted, liberation theology arises contextually within a specific sociopolitical context. Thus, to be a properly “Black Theology,” it must be connected to the Black joy and suffering that comes from the African American experience of racism. This strategically conflates Marxist ‘joy’ and ‘resilience’ (revolutionary mania and despair) with the strength of those who have endured slavery.

While I am barely touching the surface of Cone, his shadow over the so-called “Black Church” in the United States, or other relevant Black liberation theologians, please keep these theological themes in mind, particularly as it relates to figures like Dr. Thema Bryant, also a minister in AME church.

Islamic Liberation Theology

This section diverges from the primary focus on Marxified ‘Christian’ theology and cannot be adequately addressed within the boundaries of this specific piece. However, it is ultimately necessary to briefly include it for context.

Islamic liberation psychology is very much a thing, including in therapy rooms in the United States right now. It also possesses enough similar themes (prophetic activism, struggle on the side of the oppressed, Communist eschatology) that make it worth including.

Speaking generally, Islamic liberation theology interprets Islam as a transformational sociopolitical force that immanently advances (Communist, stateless, classless) Social Justice. Thus, it views revolutionary praxis as foundationally connected to the faith.

One prominent figure is the Iranian revolutionary and sociologist Ali Shariati (1939-1977), often considered the intellectual father of the 1979 Revolution that brought Ayatollah Khomeini and the current regime to power (who promptly discarded the “red” revolutionaries to preserve a “black” theocracy).

“I have no religion, but if I were to choose one, it would be that of Shariati's. – Jean Paul Sartre

Shariati spent time at the University of Paris for his graduate studies, where he started collaborating with the Algerian National Liberation Front, began engaging with the postcolonial work of Frantz Fanon, and brought it back into revolutionary Persian circles.32

Among his most significant contributions is a revolutionary revival of “Red Shiism” (the religion of martyrdom, linked to the important Shia religious figure of Ali), positioned as a purer religion against a passive “Black Shiism” (the religion of mourning, linked to the Safavid dynasty) empowering monarchy and traditional clerics.33

For those who aren’t familiar with Islam, the Shia branch comprises only 10-15% of the Muslim population versus the more dominant Sunnis and tends to be concentrated in the “Shia Crescent” of Iran, Iraq, western Afghanistan, Syria, Bahrain, and Lebanon, often facing persecution in areas where it is a minority.34

Of course, the 1979 Revolution brought Black Shiism to power in Iran, and we must be aware of this fact in the context of our modern “watermelon” revolutionary alliance.

Another foundational figure is Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966), the highly prolific Egyptian political theorist, leader in the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) after the overthrow of the monarchy, and ostensibly intellectual founder of Islamism.

Qutb is a foundational figure in understanding modern Salafi Jihadism, with clear influence over people like Osama bin Laden (al-Qaeda).35

Among other things, he was highly critical of modernity and post-Enlightenment Western civilization, believing it to be spiritually numbing, mechanical, and selfish.

In the late 1940’s, the Egyptian monarchy sent him to a highly conservative town in Colorado for two years with the apparent aim of radicalization. Instead, the very frustrated Qutb spent his time raging over the haircuts, dancing, jazz music, perceived lack of modest dress (in conservative 1940’s America), individual freedom, mixing of genders in everyday life, and support for Israel.36

He returned to Egypt more radical and ultimately participated in the 1952 overthrow of the monarchy. His involvement with the Muslim Brotherhood, however, would bring about his arrest in 1954, leading to a 15-year prison sentence. After a brief health-related release in 1964 and subsequent conviction of treason in 1965, Qutb was executed in 1966 at the age of 59.37

Among his intellectual and theological contributions include:

Interpreting pre-Islamic ignorance (jahiliyya) as a characteristic of modern society.38

The revolutionary pursuit of a “realistic utopia” meant to come about through the harmony of an allegedly social human nature and Islamic law.

Using Islamic beliefs about the oneness of God (tawhid), and thus God’s absolute sovereignty (hakimiyyat Allah), to facilitate consciousness of oppression and rejection of existing powers.39

This summary barely scratches the surface, but please note the similarities, especially regarding the use of Marxist dialectical critique, apocalyptic martyrdom, and reinterpretation of religious texts, doctrines, and historical figures.

A Psychology of Liberation

Returning to Latin America, it’s now time to review liberation psychology as a direct outgrowth of Liberation Theology.

While the term ‘liberation psychology’ was first used in 1976 by Argentinian psychologists (in the framework of Marxist Lucien Sève), the primary founder of Liberation Psychology is Spanish-born Jesuit priest and social psychologist Ignacio Martín-Baró, who was trained at the University of Chicago and lives in El Salvador.

In the 1970s, the so-called “crisis in social psychology” challenged the field’s social relevance, claims of scientific neutrality, and “pretension of universal validity.”

Here, Martín-Baró sought to respond to perceived Eurocentric and oppressive biases by developing a ‘truly’ liberatory (salvific revolutionary) paradigm.40

Importantly, this is distinct from the crisis in North American and European academia, which shifted to postmodern and idealist frameworks or returned to empiricism.

For Latin America, the response was the initiation of the ana-dialectical or so-called “analectic turn,” following Dussel, with a “new interlocutor” of the poor, meaning that:

The concepts and theories of psychology are interrogated “from below” (the standpoint of the poor and oppressed), framed in true Marxist form not as “deny[ing]” psychology but “complet[ing]” it.

The question of oppression and liberation is ontological (one of being, existence), not epistemological (one of knowledge), and resists language and “ideology” as masks for the material reality of the proletariat.

Following Marx’s 6th Thesis of Feuerbach, man is viewed as fundamentally social, “taking seriously the idea that ‘the human essence is the ensemble of social relations.’”41

This makes it notably materially oriented in comparison to the postmodern critical reflexivity best known in academia, explicitly rejecting North American critical psychology in lieu of “action-oriented psychologies of liberation” that allow for the “precedent of insurgent social movements (including the armed struggle).”42

It is this response to the crisis of social psychology that Martín-Baró developed his liberation psychology.

Appointed academic vice-rector and head of the Psychology Department in 1981, he worked at the Catholic Central American University San Salvador and would ultimately be murdered alongside other academic priests by a Salvadorean ‘death squad’ in 1989.43

Writing during the civil war, he published Action and Ideology and System, Group, and Power in 1983 and 1989, respectively, which integrated psychological theory into sociological and liberation theological-flavored political analysis.

His most well-known work, Towards a Liberation Psychology (“Hacia una psicología de la liberación”), was published in 1986, outlining essential elements for liberation psychology, including:

A new horizon for psychology, “switch[ing] focus from itself…and self-define as an effective service for the needs of the numerous majority,” meaning the purpose of psychology is to facilitate revolution for the proletariat.

A new epistemology, in which “the truth of the Latin American people is not to be found in its oppressed present, but in its tomorrow of freedom; the truth of the numerous majorities is not to be found but to be made.” This turns “truth” into Communist activism and resistance.

A new praxis, following this view of epistemology, which requires changing reality to invert praxis (recondition society). According to Martín-Baró, “to acquire new psychological knowledge it is not enough that we base ourselves in the perspective of the people; it is necessary to involve ourselves in a new praxis, an activity that transforms reality, allowing us to know it not just in what it is but in what it is not, so thereby we can try to shift it towards what it should be.”44

Following its Liberation Theological predecessor, this is a “psychology “of the feet in the sense that the psyche is not “studied” but uncovered through revolutionary practice on the part of the proletariat.

In 1998 the first International Conference was held in Mexico City, and there has since been twelve more, as well as a handful of short-lived academic journals.45

Likewise, there are parallel developments in Latin America and beyond that are worth briefly mentioning here, including:

Cuban psychology, which developed out of Marxism-Leninism into universal healthcare-oriented ‘health psychology’, following the Soviet Semashko polyclinic model, with psychological screenings and treatment embedded into every interaction with education and healthcare (sound familiar?).

Community Social Psychology, which is importantly not “ameliorative” North American community psychology but the “more radical [Latin American] liberation psychology perspective” born out of this Marxist analectic turn.

Palestinian resistance, where “the neocolonial realities of oppression by the settler State of Israel” have led to a “context-bound, yet globally integrative model of critical community psychology for the Arab-Palestinian concepts.46

2023 ACA President and liberation psychology proponent Edil Torres Rivera also elaborated on its critical constructivist view of ontology and epistemology, meaning a theory of existence/reality and knowledge, respectively.

Here, social reality is multiple, fluid, and intersectional, with an emphasis on Lived Experiences “without losing the collective experience.”47 Following this, knowledge is also subjective, situated, and grounded in this Lived Experience, meaning in the context of one’s positionality in the matrix of intersectional power and oppression.

In total, Torres Rivera identifies the following core principles of Liberation Psychology, including in clinical applications:

Reorientation of psychology towards relevance to the oppressed majority.

Recovering historical memory, meaning “real” history before it was written from the colonizer’s perspective.

De-ideologizing everyday experience, which is to “study and analyze dominant messages in light of the experiences of those living on the margins” (and is thus thoroughly in line with the Iron Law of Woke Projection in being patently ideologizing). To quote Marx, it is “arousing [the world] from its dream of itself,” making the world “aware of its own consciousness.”

Denaturalization, like de-ideologization, involves a critical examination of notions of beliefs, assumptions, etc., that are typically taken for granted (like that there are two sexes).

Problematization, tied to conscientization, which involves “the process of critically analyzing life circumstances and the role they play on the person(s).” This is a core part of conscientization and is why everything is ‘problematic’.

Engaging with Virtues of the People (the proletariat) in the face of oppression, such as their sacrifice for the collective good or faith to change the world.

Conscientization, or awakening critical consciousness (becoming “Woke”), which is a political process of becoming conscious of the dynamics of oppression and power and developing the motivation to take action to change them (revolutionary activism).

Engaging with power dynamics, following conscientization, which is to challenge existing dynamics (like capitalism, racism, etc.) to create change.

Praxis, or focusing on action above theory (see section of Liberation Theology) to Change the World. When you see “praxis” in the context of critical constructivism and liberationism, read “revolutionary activism and resistance.”48

It’s important to note that “critical” here is in the critical theoretical sense and not “critical thinking” as you, likely an educated Westerner, would understand it.

It is, to quote Marx, the “ruthless criticism of all that exists” (alluding to Marx’s beloved Mephistopheles in Goethe’s Faust, because “everything that exists deserves to perish”).

Decolonial Paradigm

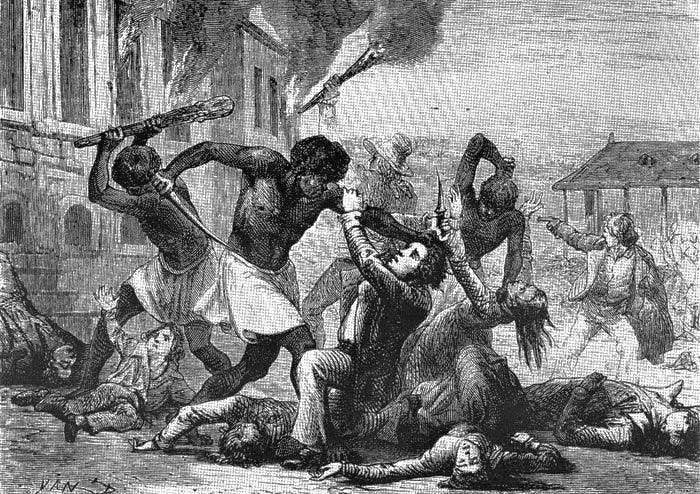

“Violence is man recreating himself.” - Frantz Fanon

Historical Movement

We will return to liberation psychology in conjunction with its decolonial partner later, but now is the time to provide context for the decolonial movement, within which the latter psychology resides.

While I cannot possibly provide the nuance and breadth it needs, decolonialism is a broad intellectual, political, and social movement that developed in response to European colonial power in parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

As you likely know, this colonialism was often tremendously evil, including the transatlantic slave trade. This bit of truth is often manipulated and exploited by mixing it with lies (e.g., that colonialism lives on through capitalism) towards revolutionary ends.

Similarly, decolonization is often framed in terms of “Enlightenment values” like liberty and self-determination. This serves as a rhetorical motte-and-bailey in which its counter-Enlightenment basis (e.g., French and German Romanticism and Idealism, French Revolution) hides behind Enlightenment ideals (e.g., Scottish Realism, American Revolution).

The brutally violent Haitian slave revolt (1791-1804), which was influenced in part by the brutally violent French Revolution (1789-1799), is often considered the first successful decolonial uprising, which should give you a sense of both where it comes from and where it is headed.

Another relevant precedent is the 1917 Russian Revolution, which overthrew the Romanov dynasty, invoking anti-imperialist rhetoric and inspiring later revolutions around the world.

After the revolution, the Bolsheviks (Social Democrats) also provided a clear historical model of DEI, indigenization (korenizatsiya), and decolonization (dekolonizatsiya) as a means of transforming a diverse empire into a socialist unity.

I encourage you to check out Steven Welliever, who has been sounding the alarm about this imported model for years, as well as this podcast from New Discourses, which reads through parts of Stalin’s rare piece of theory, “Marxism and the National Question,” to place this issue in context.

However, the decolonial movement really began picking up after the First and Second World Wars, when independence against colonial powers and the geopolitical dynamics of the Cold War facilitated waves of decolonial liberation movements in places like India, Africa, and Latin America.

During this time, some of the ‘great’ postcolonial theorists came to prominence, employing neo-Marxist critique, psychoanalysis, phenomenology, and postmodern literary theory, which were popular in the intellectual milieu.

Among the most well-known is Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), who is unusually explicit about the violence, disorder, and terror necessary to carry out “liberation.”

Fanon was a psychiatrist from Martinique whose work on colonialism, psychiatry, and race was incredibly influential in postcolonialism, critical theory, and decolonial psychology. His two best-known works, Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and The Wretched of the Earth (1961), addressed the perceived psychological effects of colonialism on both colonized and colonizer.

Throughout his work, he argued the totalizing project of colonialism includes a psychological system of dehumanization that is maintained through both physical and psychological violence, ultimately leading to alienation, identity loss, and a fractured sense of self.49

He also made it explicitly clear that violence and disorder are always a part of decolonization, requiring a cathartic, initiatory, ritual rebirth ‘in the blood’ in order to negate and overcome the initial violence of colonization.

As Fanon admits, decolonization is “quite simply the replacing of a certain ‘species’ of men by another,” in a “total, complete, and absolute substitution” as society is turned upside down. A “program of complete disorder,” the “naked truth” of which evokes “searing bullets and bloodstained knives.”50

Thus, decolonization is quite literally blood magic. The fractured sense of self and disconnection that colonization causes in the individual and community can only be overcome through this “murderous and decisive struggle,” through which both colonized and colonizer can attain salvation from from the colonized imprisonment.

It’s also worth noting that those who initiate such decolonization from a Fanonian perspective have “decided from the very beginning” to “overcome all the obstacles that [they] will come across in so doing,” understanding that decolonization’s “moving force” is “absolute violence.”

This raises questions about major professional organizations and their representatives, who advocate for a Fanonian psychology of oppression and often directly cite Fanon’s Wretched of the Earth in the mainstream academic literature.

Fanon was known to be influenced by fellow Martiniquais, poet, and politician Aimé Césaire (1913-2008), whose “Négritude movement” of literary theory sought to cultivate “black consciousness” against Eurocentrism, especially in the “Diaspora.”51

The French-Tunisian Albert Memmi (1920-2020) is also a key figure, publishing The Colonized and the Colonizer in 1957 amid many liberation movements.52

Throughout his work, he argued that colonization is harmful to both colonizers and colonized (a point echoed in Fanon’s work and relevant to the aforementioned ‘blood magic’ ritual), causing internalized inferiority in the colonized and continuing in colonial structures even after political independence is achieved.

Please also take note of the last point, as this is part of how modern post-colonial thought points to things like capitalism, “white supremacy,” and other forms of “systemic oppression” as evidence of the legacy of colonialism and systemic trauma.53

While there are many others worth noting, I will briefly conclude with the founding figure of postcolonial studies, Egyptian theorist Edward Said (1935-2003), who critiqued Western ‘constructs’ of knowledge and discourse as justifications for domination. In the context of decolonizing therapy, his theme of fragmented cultural identities and histories is critical.54

21st Century Context

To understand the decolonization issue today, it’s useful here to review exactly how a dialectical virus advances.

It’s very common for people to get hung up on the particularities and contradictions of the “Woke,” projecting their own way of thinking (truth-seeking) onto an entirely different operating system (power-seeking) that views contradictions as vehicles for advancement through dialectical critique, struggle, and sublation.

Being unable to step out of this personal frame is why many still think that critical theorists rejected Marxism, or are confused as to why the trans movement allies with Islamists.

Regardless of what you think about it, this is all entirely coherent in the Communist worldview, and it’s important to understand this to properly conceptualize and respond to their advancements.

So, when looking at the 20th and 21st-century decolonial movement, we see two ‘streams’: one of violent insurgency and class-based struggle from “below,” primarily in the so-called Global South, and another of intellectual Neo-Marxist sociocultural struggle from “above,” primarily in educated, wealthy North America and Western Europe (“Global North”).

Following its dialectical operating system, these two ‘streams’ are the ‘same in kind but different in degree,’ and thus are set in conflict and conjunction with one another with the specific aim of (violently) working out the contradictions to advance to a ‘higher’ level.

If this is new to you, I understand that may not make sense. That’s okay.

If you can, try to keep this dynamic in mind as we review the state of the 21st-century decolonial movement. Otherwise, keep reading, and hopefully, the illustration will help you connect the dots.

“As Below”

Perhaps the most significant event to kick off the 21st-century ‘era’ of decolonization was that of the September 11th terrorist attacks by al-Qaeda, a terrorist group with a clear intellectual line to the Islamist liberationism of people like Sayyid Qutb.

Among its stated political motivations included various US-led global policies perceived as colonial, including:

Support for Israel.

Support of governments against insurgency movements, like Russia (Chechnya), India (Kashmir), and the Philippines (Mindanao).

US military presence in Saudi Arabia.

US military campaigns in Somalia.

Sanctions on Iraq.55

As we know, this initiated the so-called War on Terror, including wars in Afghanistan (2001-2021) and Iraq (2003-2011), the significance of which on everything from migration to propaganda to active insurgency is impossible to address here.

Importantly, this broad Islamist movement continues today, extending into parts of Africa (especially the Maghreb), the Arabian Peninsula (like Yemen), and Southeast Asia (e.g., India, and Indonesia).

Major conflict with Israel, including the Second Intifada (2000-2005), is also relevant, and the latest round of conflict has continued to serve as decolonial fuel for sympathizers in the West.

For our purposes, the most important thing to understand is that terrorist groups like Hamas, Hezbollah, the Taliban, Al-Qaeda, and ISIS (including various Islamist offshoots in North Africa and Southeast Asia) fall within this 21st-century decolonial framework, with the United States, Western Europe, and Israel as the colonizers.

Moving very briefly to Latin America, we see multiple social and insurgency movements, with organized crime thoroughly tied up in the mix.

Uprisings over resources are common and are often tied to indigenous rights. Social and economic instability also continue, fueling migration to the “Global North” and framed in the context of ‘unsustainable capitalism’.

Similarly, most of this is pinned on things like IMF neoliberal policies and debt dependency, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and multinational corporations, resource struggles, and Indigenous rights. Taken together, these issues are particularly evocative for the 21st-century decolonial movement.

I also must acknowledge here that the United States has had a functionally open border for years, including a significant influx of ‘refugees’ from around the world aided by the United Nations and allied NGOs.

Separate from whatever you think about immigration and policy, a realistic assessment might assume a non-insignificant number of foreign enemies are currently staged domestically and allied with domestic “resistance” groups.

“So Above”

While much of the Global South is beset with material strife, the academic West has focused on postcolonial, Neo-Marxist forms of sociocultural critique (albeit very often explicitly influenced by these aforementioned movements on the ground).

Among its goals is “epistemic decolonization,” which challenges “Eurocentric” beliefs about knowledge (rational, logical, empirical, etc.) in lieu of Indigenous Ways of Knowing (IWOK), an epistemological framework centering around certain folk traditions, experiential knowledge, and “intuition.”56

Rather than fully rejecting science, Indigenous Science dialectically critiques and synthesizes its universality, objectivity, and “reductionism” toward sustainability and relationality, positioning it as more holistic and inclusive.

In reality, IWOK is selling the classic Rousseauian “Noble Savage” fantasy to buttered-up Westerners already entrenched in contrived talking points about the “mechanistic” and “selfish” legacy of Enlightenment thinking.

Pinning various global crises on “Western Ways of Knowing,” they believe that knowledge must be interconnected, communal, holistic, cyclical, place-based, centered around narrative and storytelling, and often spiritual.

If you want a glimpse at what this looks like, here’s the infamous “feminist glaciology” paper.

“Scholars” of this tradition would argue for “Two-Eyed Seeing,” a concept similar to Sandra Harding’s Strong Objectivity (feminist epistemology) that integrates both 'objective’ and ‘subjective’ into a more “holistic” understanding of the world, conferring special “sight” to those “ways of knowing” that have been excluded from the mainstream (typically for good reason)."57

This also fits within the DEI “roots-ification” indigenous strategy of the Soviets, who sold Volkish autonomy as a means of Marxifying local populations and brought Soviet representatives ‘to the table’ as stakeholders for their perspective, with the goal of “unity in content [socialism] through diversity in form.”58

Other primary objectives of this movement include:

Cultural and linguistic decolonization,” involving the revitalization of Indigenous languages/traditions and a “reclamation” of narratives in art (including literature and film).

Reparations, which include the seizure and redistribution of wealth and resources.

Indigenous sovereignty and “land-back,” meaning the return of ‘unceded territory’ (like the ground you’re likely on right now).

“Environmental justice,” represented especially in the degrowth and sustainability movements and often tied up with the alleged unsustainable exploitation of of extractive capitalism.59

“As Above, So Below”

Returning to our point about the dialectical nature of this attack, we see that these two ‘streams’ work in partnership, with the belief that any contradictions will be rightfully struggled out as they collide.

Importantly, failing to understand this dual nature and contextual legacy is why many people underestimate the extent to which they mean what they say and are signaling real intentions beyond language.

A cursory land acknowledgment at a university, for example, might be part of Neo-Marxist linguistic or cultural decolonization, with administrators often ignorant of the context and purpose.

However, this linguistic decolonization also signals a genuine plan to literally take the land back through force, and at least part of this movement is actively allying itself with those who are willing and able to help them do so.

This is the same with reparations, which are often perceived as Woke virtue signaling when, in fact, they truly mean that if given the power to do so, they will seize and redistribute wealth and resources.

Understanding these realities is incredibly important, especially in the context of certain supranational bodies like the United Nations and the facilitation of the Sustainable Development Goals.

We are not dealing with empty buzzwords from academics but explicit and active policies that will include violent insurgency and the seizure of private property if the necessary power is obtained.

Likewise, when you see “the above” (meaning North American elite academia, DEI bureaucracy, and milquetoast critical reflexivity) start to collapse, it suggests that the next stage will be a flattening of that intersectional wheel into a more populist “oppressed majority” oriented towards class struggle.

For obvious reasons, this is more likely to turn violent and disordered, and the use of decolonial and liberation psychologies cannot be untied from this reality, especially in the context of economic challenges, immigration, and similar ‘popular’ issues.

Decolonizing Psychology

Background

Against this necessary backdrop, we can now examine this in the specific context of decolonization in North American psychology and psychotherapy, considering that it has been “in” for much longer than many of us might want to admit.

Martín-Baró’s Liberation Psychology (previously discussed) could be argued as an early iteration of decolonizing therapy. Since its inception, it has had a place in the North American clinical and ‘research’ contexts, albeit more on the margins and in academia.

Similarly, there has been a clear trend to integrate "Indigenous” worldviews and practices into mental health practices, something that is relatively mainstream in many clinical contexts.

The incorporation of multicultural and feminist frameworks, represented in part by the so-called ‘fifth force” of social justice, is also relevant here, especially the belief that therapy is foundationally political.

However, 2020 and the death of George Floyd marked a turning point for the ongoing self-struggle and gutting of these fields, allowing the rapid mainstreaming of radicalism.

Thus, we will focus our attention here on how it presents within this post-2020 context.

Decolonial Psychology

Here, decolonial psychology is often used interchangeably with “Indigenous psychology” and is framed as a “cultural reclamation” against so-called colonial structures (the various -isms, with a particular focus on class, race, and national origin).60

It grounds itself in Neo-Marxist postcolonialism, especially Fanon’s psychology of oppression, which we know necessarily includes a violent ‘rebirth’ through a disordered, terroristic, and bloody uprising.

This is very important to understand, as the academic framing hides the practical implications and purpose, which is to bring about a revolution that is necessarily and explicitly violent.

Take the emphasis on decolonizing epistemology through Indigenous Ways of Knowing and so-called “counter-epistemologies” that “reimagin[e] and reshap[e] the field through epistemic justice.”61

By adopting an ‘interconnected’ and ‘holistic’ (Communist) lens, we see the various systems of power and oppression at the root of various (artificially created and propagandized) crises, especially those related to economics, national origin (immigrants), and race.

We then know that freedom cannot exist unless those perceived root causes are overcome through Communist revolution, and that those who are oppressed are called to participate in it.

In the same paper, Bryant also alludes to the practical requirements embedded within these “counter-epistemologies,” reminding us that “decolonization is not just a metaphor,” and that “healing does not merely require a freeing of their minds but also considerations of both individual and collective liberations.”

This is so important to understand, and our failure to do so is why major professional bodies can openly advocate for the facilitation of violent Communist revolution using therapy without most of the profession noticing.

Bryant’s 2023 presidential counterpart at the ACA, Dr. Edil Torres Rivera, has also been a leader in advocating decolonial and liberation psychologies.

In a co-authored paper recently published in the ACA’s Journal for Multicultural Counseling and Development, he wrote of a multistage colonization and decolonization process in counseling, directly citing Fanon’s “Wretched of the Earth” and bizarrely copy-and-pasting verbatim from another article that explicitly included a “resort to arms” in the “action” phase.62

If you have the time, I suggest reading it and asking yourself how something this radical, bizarre, and almost unreadable is published in a mainstream, allegedly double-blind peer-reviewed ACA academic journal.

Lastly, no discussion on this topic would be complete without Dr. Jennifer Mullan, a trained psychologist and author/creator of Decolonizing Therapy.

Mullan is known as the “Rage Doctor,” describing herself as an “ancestral wound worker” and “intergenerational and historical trauma alchemist,” among other things.

A psychology graduate of the California Institute of Integral Studies (a particularly radical program, as far as I can tell), she describes “bend[ing] the rules” in her work as a clinician” and thus getting “into ‘trouble a lot’.” But, according to Mullan, “[her] clients received better care, and [she] slept better at night.”

“At times I had to bend the rules. Because it was clear that these ethics, and policies weren't serving the people I was there to help. Because they weren't created with QBIPOC in mind. I got into ‘trouble’ a lot, but my clients received better care. And I slept better at night.

Over time, I became more active politically and in my communities. Those spaces fortified, educated, unraveled and invited me - not as a psychologist - but as a person who needed her own healing, and a person who would give community care as systems collapsed.

I found identity and solidarity in people outside of my field more than I did within. LGBTQ center coordinators, undoing racism activists, abolitionist teachers, ferocious librarians. I saw myself in them. People doing the real work.

I found myself breaking out of the mold with like-minded peers. Co-creating new ways of doing therapy. Ways that were about true healing and liberation.

From this collective reimagining, Decolonizing Therapy was born.”63

As a part of this work, she has also trademarked (🤡) the Colonial Soul Wound™, which is defined as “the impact of colonization on the psyche, spirit, and soul of a people + persons, leading to disconnection, disembodiment + fragmentation of the collective + self, as well as over-reliance on Western ways.”64

Directly quoting from her website, this Colonial Soul Wound™ shows up as:

Dissociation/disembodiment due to Eurocentric violence

Pervasive Soul Dehydration + Exhaustion

Conditioned colonial responses

Cyclical generational behaviors

Hypervigilance

Repressed Rage

Belief in + protection of colonial systems/rules

Minimization of Magic and Spirit

Denial/Rejection of ancestors and/or cultural practices

Over-pathologization

Fear of being seen

Given the obvious influence of postcolonial theory, a “Rage Doctor” who “alchemizes intergenerational and historical trauma” through “decolonizing therapy” is tremendously concerning.

This perspective is also echoed throughout much of current decolonial psychology, which criticizes Western psychotherapy as reductive and advocates for a holistic integration of the “whole person,” particularly as it relates to trauma.

This is music to the ears of many psychotherapists, and is likely why clinicians are particularly vulnerable to this sales pitch.

But, as Dr. Bryant makes clear in her 2023 Presidential Paper, this fractured, alienated self not only demands personal transformation (conscientization) but also collective liberation from the various systems of oppression causing trauma.65

In our current popular context, this includes capitalism, private property, the United States and its Constitution, Israel and Zionism, and similar “oppressive” systems.

Take a moment, sit, and think about what that truly means.

Thus, when decolonial psychology positions itself as “activat[ing] people” towards “holistic healing,” with a particular focus on “rehumanizing people of the Global South,” and is deployed alongside a praxis-based ‘psychology’ oriented towards ‘true’ liberation that must include the “precedent of armed struggle,” a picture begins to form that is incredibly serious.

Liberation and Decolonial Psychologies in Practice

While these psychologies are relevant in a variety of ‘mental health’ contexts, I will focus here on their (abjectly abusive) deployment in clinical and adjacent practices with vulnerable people.

Please consider this a preliminary list.

For more on these ‘psychologies’ in the research context, see my article at Correspondence Theory here.

Critical Consciousness

While we reviewed critical consciousness (“Woke”) in our discussion of liberation psychology and its background in Latin America with Freire, it is so foundational in these psychologies that it is worth returning to.

James Lindsay nailed it when he described Freire as a Revivalist figure in the Marxist religion, which had taken a pessimistic Neo-Marxist turn with the Critical Theorists.

Consider that Marxist consciousness up until that point was based on class, which poses a curious paradox for the revolutionary: how do you overcome class through class consciousness?

The proletariat’s last battle would be with itself.

For Leninists, the solution would be an increasingly dominating state apparatus through a dictatorship that would ‘wither away’ after it had effectively purged and struggled its People into full Marxist stateless classless consciousness.

Freire, however, had a different solution: adopting critical consciousness as a ‘bridge’ between class and full Marxist consciousness, involving repeated cycles of revolutionary critique and praxis.

Through this denouncement and tearing down of what exists, the possibility of hope is announced in its rubble.

Thus, critical consciousness is a repeated cycle of awakening to systems of power and oppression, the recognition that one is a historical agent who can participate in and move history toward its utopian End (Communism), and the action upon the world to change it.66

This is the foundation of social justice psychotherapy and is turbocharged in the context of decolonial and liberation psychologies.

Consciousness-in-Action

Following Freire, Integral psychologist Raul Quinones Rosado’s “consciousness-in-action” model is also worth being aware of.

Rosado “opens new ways for transmuting the processes of fear, oppression, and victimhood into liberation and transformation” by overlaying the Native American medicine wheel with the well-known AQAL (all quadrants all levels) model from Ken Wilbur’s Integral Theory.

Here, a cyclone represents the dynamics as mutually interrelated and reinforcing. Oppression moves “inward,” causing a reinforcing contraction of self-identity, and thus, liberation must move “outward” through a reinforcing process of consciousness-in-action.

This processual model builds upon Freire’s gnoseological process, using a sequenced cycle of action and reflection meant to unite awareness and will/volition into a “deliberate, disciplined, and sustained ethical response” for “personal and collective liberation.”67

While Freire’s model focuses more on structural transformation through critical awareness of oppression, this model uses Integral Theory to incorporate psychology, spirituality, and social engagement.

This allows it to be sold as more holistic and personal for the clinical context, keeping the Freirean Marxist core and facilitating sustained revolutionary action against any pushback and failure.

Ancestral Knowledge/Indigenization

As Dr. Thema Bryant noted in her column for the APA, a central part of decolonizing psychology is in the incorporation of so-called Indigenous Science, which falls more broadly under the umbrella of Indigenous Ways of Knowing (IWOK),

In her article on decolonial and liberation psychologies for trauma, Bryant also cites various African-centered psychotherapeutic approaches, including Sankofa psychotherapy, whose namesake comes from a West African proverb that roughly translates to “it is not taboo to fetch what you forgot,” meaning (generously) to learn from the past to build the future.68

Importantly, this is an explicitly decolonizing, “integrative, psychoecocultural” intervention grounded in the idea that “disconnection” (lack of Communism) is the central driver of psychological disorder and thus (re)connection drives healing, employing the Sankofa 7s (7 Wisdoms, 7 Sankofa Reconnection Process, 7 Domains of Interconnectedness, etc.).69

The Association of Black Psychologists (ABPSI) is also offering Sawubona (“I see you”) Healing Circles, which are virtual and in-person cultural groups that “while not therapy, integrate ancestral wisdom with African-centered strategies rooted in Ubuntu (‘I am because we are’),” a proverb that brings to mind Paulo Freire’s (Communist) ontological declaration that “the ‘I exist’ does not precede the ‘we exist’ but is fulfilled by it.”

According to the ABPSI, the goals of these Healing Circles include, among others, “promot[ing] culture, resistance, and alignment with African-centered principles,” as well as “strengthen[ing] community self-care and activate self-healing,” which has strong implications in context.70

Unfortunately, and I say this with sincere trepidation but necessary warning, a great deal of marketed “African-centered principles” are highly Communist and serve to target African Americans as a tool for revolution. The contrived holiday of Kwanzaa, with its alleged seven “pan-African” principles that include things like “collective work” and “cooperative economics,” is a good example.

Decolonial psychology also frames “Western” (logos-based) practices like talk therapy as Eurocentric and inherently harmful, pushing pathos-oriented ‘ancestral’ work instead.

This can include everything from “somatic” work to entering altered states of consciousness and attempting to commune with or receive downloads from ancestors. I’ve personally seen multiple public therapy ads that advertise the latter.

A similar line of deployment is ‘brujeria’, syncretic witchcraft that has become popular on social media (and clinicians), and can include things like potions, seances/attempts to ‘commune with ancestors’ (see ‘downloads’), tarot, and other so-called ‘indigenous’ practices. These are framed as “stigmatized” from the colonial perspective and thus must be recovered and practiced as a means of resistance.71

Diagnosis/Reporting

A central part of decolonial and liberation psychologies also involves the rejection of the DSM as fundamentally bigoted and harmful, in part because it follows a ‘Western’ scientific framework versus these more ‘holistic’ Indigenous Ways of Knowing.

They also tend to eschew many diagnoses due to “stigma” and are ethically empowered to refrain from diagnosis if they think it could be “stigmatizing.” Naturally, the most stigmatizing are usually some of the most debilitating, so those in most need of effective treatment are less likely to receive it.

As an alternative, researchers and practitioners advocate for the use of vague ‘alternative’ pseudo-diagnoses like intergenerational trauma, Post-Colonial Stress Disorder (PCSD), which is caused by systemic oppression, or the Colonial Soul Wound™.72

These are usually evidenced by things like stress, burnout, belief in “colonial” frameworks like individualism or free markets, low self-esteem, a lack of “Magic” and “Spirit,” and similarly vague, common symptoms.

Kafka traps within this are also common. Anything a client does (or doesn’t do) is evidence of one of these decolonized “diagnoses,” and the “treatment” virtually always includes participation in collectivist activism and resistance.

Thus, decolonial and liberation psychologies not only make it more likely that those who are seriously mentally ill are not adequately diagnosed and treated, but also provide an opportunity to abuse the appearance of authority as a licensed clinician to present the (Marxist cult conspiratorial) idea that systemic oppression is the cause of one’s issues, and that participating in the revolution is the only way to resolve them.

Practitioners are also more hesitant to call the police, which they believe perpetuates harm, and thus are less likely to carry out their mandated reporting duties for both suicidal and homicidal risk.

Consider that these are often the most materially and psychologically vulnerable populations, and are being intentionally radicalized against conspiratorial powers often tied up with large demographics of innocent people, and you’ll see how absolutely horrifying this situation is.

Recovering Historical Memory

Another primary tool is “recovering historical memory,” which involves examining current societal structures of privilege and power (raising critical consciousness), identifying ways in which colonization and oppression have allegedly ‘re-written’ the ‘history’ of various collective identities, and recovering the groups ‘true’ history free from the colonizer’s erasure.

This is generally presented (in peak Iron Law of Woke Projection form) as “de-ideologizing” experience and “denaturalization,” freeing clients of the “cultural stranglehold” of their imprisoning social structure and allowing them to recover their Authentic Self.

The ultimate goal is to help clients “in gaining awareness regarding the structural barriers, messages that have been passed through generations, and how thoughts, perceptions, and actions have been perpetuated throughout their history.”73

Importantly, intentionally developing a sense of collective identity and then utilizing (real or imagined) historical oppression is an established radicalization technique.

The former Ayatollah Khomeini, for example, exploited historical Shia oppression as a part of building support for his movement, which would go on to overthrow the Shah in the 1979 Revolution and create various Shiite insurgency movements (like Hezbollah) in the region.74

Virtues of the People

As noted previously, these are Communist virtues identified within the oppressed (proletariat).

This typically hides behind “strengths-based” language, moving beyond “deficit thinking” and “resilience” language, and generally includes courage (to resist oppression), solidarity (to come together as an identity group), faith (that they can change the world), and hope (for their “tomorrow of freedom”).75

What can be, unburdened by what once was.

Thus, this “strengths-based approach” serves as a critical part of the conscientization process, helping to build a sense of personal agency, solidarity, and hope for a Communist utopia that will never come.

Testimonios

“Testimonios” is a clinical technique for raising critical consciousness that also comes directly from Martín-Baró’s liberation psychology.

Here, clients participate in a mindfulness grounding exercise (facilitating a relaxed alpha brain wave state conducive to brainwashing) and are then led to share their experiences with oppression (at times by therapist self-disclosure of their own identity-based experiences) and healing, with a focus on “embracing their collective identities.”76

This follows a postmodern approach that views language as constructing (versus describing a discovered) reality and is used to connect various isolated life experiences into an imposed systemic (conspiratorial) power structure, which can only be addressed through total revolution.

Also, consider how easy it is to accurately document this in the notes in a way that massively underplays the seriousness of the intervention.

Say a client comes in with financial challenges and is stressed. I could pivot to a “grounding exercise” and then lead them in a “narrative approach” (testimonios) where we talk about how rents are out of control, even speaking of my own struggles. I can then end with “psychoeducation” (about oppression and historical agency) and assign “problem-solving” homework that involves Communist activism and resistance.

All of this could likely be billed to insurance, and I would be fully honest about what was going on in session and fully comply with legal, ethical, and other professional oversights.

Problem-Solving Coping

Lastly, “problem-solving coping” in the form of “resistance” is positioned in contrast to “emotion-focused coping” typical in Western, non-liberationist forms of therapy.

According to Dr. Bryant, such resistance “may include, but [is] not limited to, filing a complaint, leaving a job, running for office, marching, boycotting, organizing a community response, advocating for policy change, and confronting the persons perpetrating the stress and trauma of oppression.”77

This means that activism and resistance are considered therapeutic, among which include vaguely worded “confrontation.”

What now?

Although much of it was necessarily brief, we covered a great deal of information here, so let’s review some of what we know.

We can say that liberation and decolonial psychologies come from Marxified paradigms that advance dialectically (that is, through periods of critique and sublation), and that their current popular position vis-à-vis critical reflexivity and social justice is to advance the target deeper into radicalism, in this case the ‘mental health’ field and the people it’s meant to serve.

We know that they aim to facilitate Marxist revolutionary consciousness and action, with the aim to destroy the existing economic, sociopolitical, cultural, and psychological state.

This includes the end of the United States, its Constitution, cognitive liberty, free markets, and private property.

We can recognize that participation in this necessarily violent, disordered, and terroristic struggle is perceived as salvific for both victim and perpetrator, framed in the context of psychology and counseling as healing.

We know these ‘psychologies’ are practiced through techniques and frameworks like:

Critical consciousness-raising (conscientization) and consciousness-in-action

Testimonios

Recovering historical memory

De-ideologization and de-naturalization

Indigenous Ways of Knowing

Ancestral practices that include witchcraft, communing or receiving ‘downloads’ from spirits, imagination, and similar practices

Problem-solving coping like activism and resistance, including “confrontation”

We can also recognize that these are established radicalization tactics for terrorism and insurgency movements, which fit within their stated purpose of conscientization and the facilitation of revolutionary insurgency.

Thus, we can say with confidence that the mental health fields are using the professional role, including and especially therapy, to radicalize vulnerable people into violent, seditious Communist revolution.

This fact, which may still be difficult to wrap your head around, means that there is tremendous harm going on in the mental health fields, and one could make the case that the professions are operating in open sedition against the United States using the very people seeking help as fuel to throw into the furnace for revolution.

Take a moment, sit with that, and consider the evil and harm.

So, what can we do?

First, don’t take the sales pitch and participate.

This is extremely serious stuff, highly unethical, probably illegal, and eventually, the truth comes out. There are going to be a lot of stupid people who participated in something patently above their real pay grade with this, and you don’t want to be one of them.